Difference between revisions of "Python:Iterative Structures"

(→Examples) |

(→Indexing Items) |

||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

== Indexing Items == | == Indexing Items == | ||

| − | While using a loop, you may want to access certain elements of | + | While using a loop, you may want to access certain elements of sequences within that loop. To do this, you will need a variable that holds on to the index number you want to access. There are at least three different ways to create this variable: using the loop scanning variable itself as in index, using the <code>enumerate</code>function to generate a table of index and value pairs, or creating an external counter. |

=== Scanner Variable === | === Scanner Variable === | ||

| − | If you have a loop that is meant to go through a pre-determined number of iterations, | + | If you have a <code>for</code> loop that is meant to go through a pre-determined number of iterations, you can set up the loop variable to keep track of what iteration you are on: |

| − | < | + | <syntaxhighlight lang="python"> |

| − | for | + | for k in range(12): |

| − | + | # Code | |

| − | + | </syntaxhighlight > | |

| − | </ | + | For instance, to obtain twelve different values from a user, you can use the following code: |

| − | + | <syntaxhighlight lang="python"> | |

| − | < | + | temperatures = [None]*12 |

| − | + | for k in range(12): | |

| − | for | + | temperatures[k] = float(input('Enter a temperature: ')) |

| − | + | </syntaxhighlight> | |

| − | + | This uses the fact that <code>k</code> takes on the values of 0, 1, 2, 3, etc., which will work as your index variable. The <code>temperatures</code> list will end up with the twelve values the users gave you. Of course, in Python if you are just building a list, you can also append things to the list without worrying about the index: | |

| − | </ | + | <syntaxhighlight lang="python"> |

| − | + | temperatures = [] | |

| + | for k in range(12): | ||

| + | temperatures += float(input('Enter a temperature: ')) | ||

| + | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Enumerated Iterable === | ||

| + | If you are iterating over something that cannot be used as an index - for example, the characters in a string - you can use the <code>enumerate</code> function to return an iterable that replaces each item with a tuple containing the index and value of the item. The <code>enumerate</code> type is similar to <code>range</code> and <code>map</code> in that it does not have a good way of showing what it is actually equal to -- for that, you need to recast it as a list. For example, assuming you have run the following code: | ||

| + | <syntaxhighlight lang="python"> | ||

| + | my_words = 'Go Duke!' | ||

| + | my_enum = enumerate(my_words) | ||

| + | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| + | then | ||

| + | <syntaxhighlight lang="python"> | ||

| + | print(my_enum) | ||

| + | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| + | yields | ||

| + | <syntaxhighlight lang="python"> | ||

| + | <enumerate object at 0x000001BF3194C2D0> | ||

| + | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| + | while | ||

| + | <syntaxhighlight lang="python"> | ||

| + | print(list(my_enum)) | ||

| + | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| + | yields: | ||

| + | <syntaxhighlight lang="python"> | ||

| + | [(0, 'G'), (1, 'o'), (2, ' '), (3, 'D'), (4, 'u'), (5, 'k'), (6, 'e'), (7, '!')] | ||

| + | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| + | You can now run a <code>for</code> loop on the results of the <code>enumerate</code> command; if you have two scanning variables, the first will pick up an index and the second will ipck up the value: | ||

| + | <syntaxhighlight lang="python"> | ||

| + | for idx, val in enumerate(my_words): | ||

| + | print('idx: {} val: {}'.format(idx, val)) | ||

| + | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| + | yields: | ||

| + | <syntaxhighlight lang="python"> | ||

| + | idx: 0 val: G | ||

| + | idx: 1 val: o | ||

| + | idx: 2 val: | ||

| + | idx: 3 val: D | ||

| + | idx: 4 val: u | ||

| + | idx: 5 val: k | ||

| + | idx: 6 val: e | ||

| + | idx: 7 val: ! | ||

| + | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| + | |||

=== External Variable === | === External Variable === | ||

| − | Sometimes, you will not have an integer-based scanning variable - or you may not have a scanning variable at all (example: while loops). For those, you may have to start an external counter. For example, if you want to store temperature inputs so long as the temperatures entered are non-negative, you could write: | + | Sometimes, you will not have an integer-based scanning variable - or you may not have a scanning variable at all (example: <code>while</code> loops). For those, you may have to start an external counter. For example, if you want to store temperature inputs so long as the temperatures entered are non-negative, you could write: |

| − | < | + | <syntaxhighlight lang="python"> |

| − | + | num_temps = 0; | |

| − | + | temperatures = [] | |

| − | + | temp_in = float(input('Enter a temperature (negative to stop): ')) | |

| − | while | + | while temp_in >= 0: |

| − | + | num_temps += 1 | |

| − | + | temperatures += [temp_in] | |

| − | + | temp_in = float(input('Enter a temperature (negative to stop): ')) | |

| − | + | </syntaxhighlight > | |

| − | </ | + | At the end of this code, <code>num_temps</code> will be a value that indicates how many entries there are in the <code>temperatures</code> list. |

| − | At the end of this code, | ||

== Initializing Large Vectors == | == Initializing Large Vectors == | ||

Revision as of 15:46, 15 September 2019

Often in solving engineering problems you will want a program to run pieces of code several times with slightly - or possibly vastly - different parameters. The number of times to run the code may depend on some logical expression or on the number of columns in a particular matrix. For these, you will use iterative structures.

Contents

Introduction

There are two main iterative structures in Python: while loops and for loops. A while loops is controlled by some logical expression which is evaluated before deciding whether to run the code it controls. If the expression is true, the while loop will run the code it controls and once that code is done executing, it will reevaluate the logical expression. The loop will keep running until the logical expression is false at the time it gets evaluated.

A for loop on the other hand has a variable that scans through the entries in some iterable item (for example a list, tuple, array, range, map, string, dictionary). The variable takes on the 0 indexed value of the item and runs the code it controls; once that code is done, it will take the next item from the sequence. The for loop will run as many times as there are items in the sequence.

In both for and while loops, there are two commands that will change the behavior of the loop a bit. If you issue the continue command, the loop will immediately skip to its own end as if the code block were over. A while loop would then evaluate the logical expression again and re-run its code if the expression is still true; a for loop will grab the next item from the sequence if there is on. The other command that changes how a loop behaves is a break; if a loop runs a break command it will skip out of the loop immediately.

Examples

while loops

Imagine you want a user to enter a number between 0 and 10 inclusive; in cases where they get it wrong, you want them to try again. You might start your code by getting an input from the user:

x = input('Number in range [0, 10]: ')

If you run this code, you will realize that Python's input command renders whatever you give it as a string. To fix that, you can tell Python to re-cast it as a float:

x = float(input('Number in range [0, 10]: '))

This works, but it neither checks to see if the user actually entered a numerical type nor does it check if the value is in the right range. Because you will want the user to keep entering values until something valid is entered, you will use a while loop to evaluate the answer and get another value:

x = float(input('Number in range [0, 10]: '))

while x < 0 or x > 10:

x = float(input('Incorrect value - number in range [0, 10]: '))

This now does exactly what you want it to do, as long as the user has given an input that can be rendered as a float. If the user enters a non-numerical character, Python will give an error. If you want to deal with that situation, you will need to check what the user gives as an input before trying to make it a float. This is complicated by the fact that Python does not currently have a great way to check if the contents of a string can represent a float. Given that, it might be easier to use Python's try structure and then catch and display any exceptions. Here's an example that takes advantage of try, continue, and break to first see if the string entered could be turned into a float and, if it can, if that float is in the proper range:

x = input('Number in range [0, 10]: ')

while 1:

try:

x = float(x)

except Exception as oops:

print(oops)

print('"{}" contains invalid characters'.format(x))

x = input('Number in range [0, 10]: ')

continue

if x < 0 or x > 10:

x = float(input('Incorrect value - number in range [0, 10]: '))

else:

break

Note the use of while True here; this loop will run indefinitely on its own - the only thing that causes it to stop is if the break happens.

for loops

The following codes will demonstrate different ways to scan through the entries of an iterable:

Scanning through a list (or tuple, or array)

for k in [3, 1, 4, 1, 5]:

print(k)

Scanning through a string

for k in 'Hello!':

print(k)

Scanning through a range (or map)

for k in range(3, 7):

print(k)

Scanning through a dictionary

Assume the following code has run to create a dictionary d:

d = {}

d[4]='hello'

d['Duke']=1.234

d[(20,19)] = [20, 23]

such that d is now:

{4: 'hello', 'Duke': 1.234, (20, 19): [20, 23]}

There are four ways to scan through it:

for k in d:

print(k)

for k in d.values():

print(k)

for k in d.items():

print(k)

for p, q in d.items():

print('p: {}, q: {}'.format(p, q))

Indexing Items

While using a loop, you may want to access certain elements of sequences within that loop. To do this, you will need a variable that holds on to the index number you want to access. There are at least three different ways to create this variable: using the loop scanning variable itself as in index, using the enumeratefunction to generate a table of index and value pairs, or creating an external counter.

Scanner Variable

If you have a for loop that is meant to go through a pre-determined number of iterations, you can set up the loop variable to keep track of what iteration you are on:

for k in range(12):

# Code

For instance, to obtain twelve different values from a user, you can use the following code:

temperatures = [None]*12

for k in range(12):

temperatures[k] = float(input('Enter a temperature: '))

This uses the fact that k takes on the values of 0, 1, 2, 3, etc., which will work as your index variable. The temperatures list will end up with the twelve values the users gave you. Of course, in Python if you are just building a list, you can also append things to the list without worrying about the index:

temperatures = []

for k in range(12):

temperatures += float(input('Enter a temperature: '))

Enumerated Iterable

If you are iterating over something that cannot be used as an index - for example, the characters in a string - you can use the enumerate function to return an iterable that replaces each item with a tuple containing the index and value of the item. The enumerate type is similar to range and map in that it does not have a good way of showing what it is actually equal to -- for that, you need to recast it as a list. For example, assuming you have run the following code:

my_words = 'Go Duke!'

my_enum = enumerate(my_words)

then

print(my_enum)

yields

<enumerate object at 0x000001BF3194C2D0>

while

print(list(my_enum))

yields:

[(0, 'G'), (1, 'o'), (2, ' '), (3, 'D'), (4, 'u'), (5, 'k'), (6, 'e'), (7, '!')]

You can now run a for loop on the results of the enumerate command; if you have two scanning variables, the first will pick up an index and the second will ipck up the value:

for idx, val in enumerate(my_words):

print('idx: {} val: {}'.format(idx, val))

yields:

idx: 0 val: G

idx: 1 val: o

idx: 2 val:

idx: 3 val: D

idx: 4 val: u

idx: 5 val: k

idx: 6 val: e

idx: 7 val: !

External Variable

Sometimes, you will not have an integer-based scanning variable - or you may not have a scanning variable at all (example: while loops). For those, you may have to start an external counter. For example, if you want to store temperature inputs so long as the temperatures entered are non-negative, you could write:

num_temps = 0;

temperatures = []

temp_in = float(input('Enter a temperature (negative to stop): '))

while temp_in >= 0:

num_temps += 1

temperatures += [temp_in]

temp_in = float(input('Enter a temperature (negative to stop): '))

At the end of this code, num_temps will be a value that indicates how many entries there are in the temperatures list.

Initializing Large Vectors

One of the dangers in MATLAB's ability to automatically resize a vector is the amount of time it actually takes to do that.

Iterative Resizing

Consider the following:

clear

tic

y0 = 0;

v0 = 5;

a = -9.81;

NP = 10;

t = linspace(0, 5, NP)

for k=1:NP

y(k) = y0 + v0*t(k) + 0.5*a*t(k).^2;

end

toc

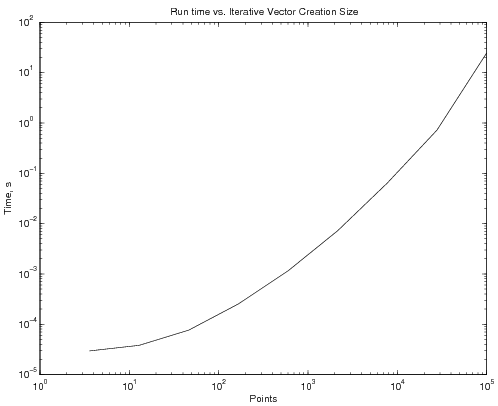

This code takes, on average, 36 microseconds to run. If NP is increased to 100, the average time to complete goes up to about 150 microseconds. NP of 1000 increases the time to 2.25 ms. And NP of 100000 increases the time to over 10 s! The graph below shows, on a log scale, time to complete as a function of NP:

Clearly, this becomes a major problem as the number of points increases.

Initialized

Remarkably, adding a single line completely changes the timing of the program. The following program:

clear

tic

y0 = 0;

v0 = 5;

a = -9.81;

NP = 10;

t = linspace(0, 5, NP)

y = t*0; % here's the only thing that changed!!!

for k=1:NP

y(k) = y0 + v0*t(k) + 0.5*a*t(k).^2;

end

toc

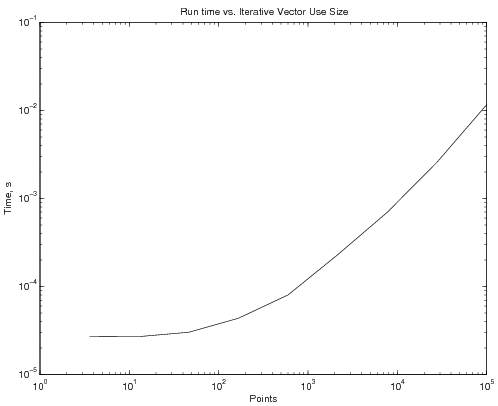

generates the following time vs. NP graph:

which indicates a reduction, by three orders of magnitude, of the run time. And all that was done was creating a vector y of the appropriate size before running the loop, rather than continuously changing the vector size inside the loop.

Vectorized

Of course, the fastest version of the code uses MATLAB's ability to vectorize:

clear

tic

y0 = 0;

v0 = 5;

a = -9.81;

NP = 10;

t = linspace(0, 5, NP)

y = y0 + v0*t + 0.5*a*t.^2;

toc

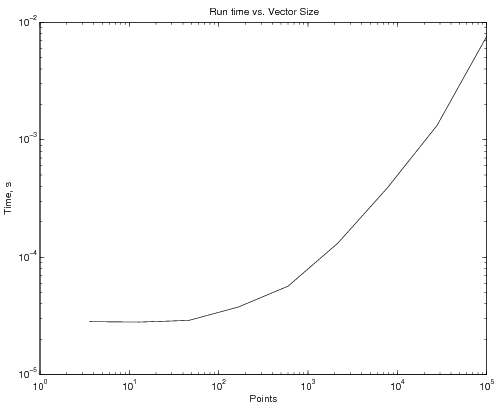

which generates the following time vs. NP graph:

Questions

Post your questions by editing the discussion page of this article. Edit the page, then scroll to the bottom and add a question by putting in the characters *{{Q}}, followed by your question and finally your signature (with four tildes, i.e. ~~~~). Using the {{Q}} will automatically put the page in the category of pages with questions - other editors hoping to help out can then go to that category page to see where the questions are. See the page for Template:Q for details and examples.